I’m coming off a long stretch of women confessing abortions to me. They are confessing because they are scared…and looking for hope.

I know some of you may be thinking that I’m hitting on a bunch of political topics these days. Yes, I am. But in this article you will not find photos of unborn children or the usual pro-life message. My thoughts go soul deep. You will not find guilt-tripping or politics-as-usual because it’s not just usual politics in the lives of women I meet. It’s personal to them. They’re frightened because it’s their story and they’re looking for answers to questions. They’re looking for hope.

I’m writing about this today because good politics arise out of good theology. If one’s worldview is to be consistent, that is. Whether your worldview is one that includes God or not, it’s not a cafeteria where you choose some from each group, a knife and a fork, and head to the cashier.

I’m writing about this today because good politics arise out of good theology. If one’s worldview is to be consistent, that is. Whether your worldview is one that includes God or not, it’s not a cafeteria where you choose some from each group, a knife and a fork, and head to the cashier.

Presently, the Democratic National Convention is underway in the United States. Numerous women are scheduled to speak, ostensibly on behalf of American women.

* * *

They do not speak for me.

They do not speak for me because I hold a well-developed theology on the Image of God. These women, because of their views, simply cannot speak life to any woman who thinks theologically as I do.

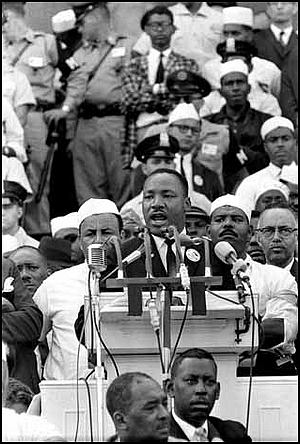

In the previous article, Asking All the Wrong Questions about Discrimination, I outlined the necessity of holding a high view of the Image of God and asserted that this is our way to solving the racial divide. Likewise, a well-developed understanding of the Image of God ought to inform our views on abortion.

There is a wrong question out there: Should there be limits on a woman’s right to choose?

There are many reasons this is a wrong question.

- The first one is grammatical. “To choose” –a verb—typically needs an object for the sentence or question to make sense. One needs “to choose” something whether it is a choice to do or not to do, or a choice among alternatives. The implied object in the question above is abortion. If the object were different (substitute anything you choose and see for yourself), the whole question changes. As does the answer. The meaning and the value given to the object are what determine the rightness of the choice.

- Sometimes the word choice just reflects a manner of choice as in “Choose wisely.” But even Indiana Jones knows the choice is among alternatives (e.g. to drink from the Holy Grail or select a different cup). The alternatives have consequences, if the choice truly makes any difference. What are the implied options in the question above? Choose what? You know the two answers. There is no half-life or anything in between.

Then, there’s the issue of whether it’s any person’s right to choose. At present, Roe v Wade has been a turning point, giving a woman a right to choose an abortion because it’s her body in which the baby is formed. This is the legal premise on which a woman has a choice. What our wrong question presumes is that we can discriminate in favor of one party. No wonder it’s a coveted “right” for so many women. I know some of you will find this offensive, but it’s the same selfishness behind slave owners having liked the choice–the right–to have Negro slaves, even though it would have not been the choice of the person enslaved nor those who sought emancipation for them. If the object of the question were “to choose gradual eradication of black Americans,” a woman’s right to choose seems significantly less noble and far more horrific, does it not? Consider this: “Abortion kills more black Americans than the seven leading causes of death combined, says Centers for Disease Control data,” according to published news reports. BlackDignity.org writes:

Then, there’s the issue of whether it’s any person’s right to choose. At present, Roe v Wade has been a turning point, giving a woman a right to choose an abortion because it’s her body in which the baby is formed. This is the legal premise on which a woman has a choice. What our wrong question presumes is that we can discriminate in favor of one party. No wonder it’s a coveted “right” for so many women. I know some of you will find this offensive, but it’s the same selfishness behind slave owners having liked the choice–the right–to have Negro slaves, even though it would have not been the choice of the person enslaved nor those who sought emancipation for them. If the object of the question were “to choose gradual eradication of black Americans,” a woman’s right to choose seems significantly less noble and far more horrific, does it not? Consider this: “Abortion kills more black Americans than the seven leading causes of death combined, says Centers for Disease Control data,” according to published news reports. BlackDignity.org writes:

In America today, almost as many African-American children are aborted as are born. A black baby is three times more likely to be aborted as a white baby.

“Since 1973, abortion has reduced the black population by over 25 percent. Twice as many African-Americans have died from abortion than have died from AIDS, accidents, violent crimes, cancer, and heart disease combined.”

“80 percent of abortion facilities are located in minority neighborhoods. About 13 percent of American women are black, but they receive over 35 percent of the abortions.”

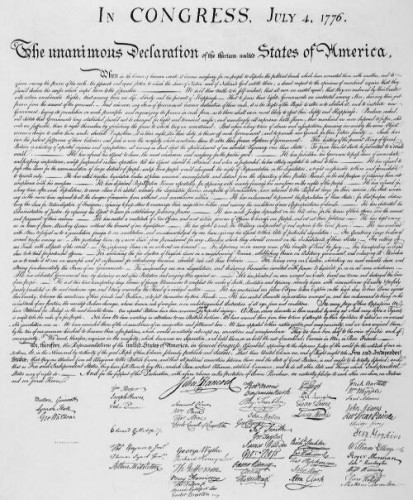

4. A fourth reason (and there are many others) that this is a wrong question is that a society without limits, by definition, exhibits anarchy. There must certainly be limits and laws to keep our society from becoming a lawless place where one person’s right to choose results in the extermination of other people.

Let me say this differently: When a choice involves one class of people’s “right to choose” and results in selective and intentional elimination of another class of people because the powerful choosers have determined that the vulnerable have little or no utility, this is not a social good.

In China, the death toll among girl babies has been astronomical. According to researchers, this year alone perhaps a million have been aborted and tens of thousands abandoned. As the BBC captions this photo of a boy, “Boys are considered much more useful than girls” and quoting a Chinese mother, “Boys are best, because they can work.”

In China, the death toll among girl babies has been astronomical. According to researchers, this year alone perhaps a million have been aborted and tens of thousands abandoned. As the BBC captions this photo of a boy, “Boys are considered much more useful than girls” and quoting a Chinese mother, “Boys are best, because they can work.”

Boys have utility. Girls don’t.

In America we might do fewer gender-selective abortions, but perceived utility for the chooser is the driving factor nonetheless.

So the debate becomes focused on when life begins.

If the embryo has fullness of life and a woman were to choose to abort it; if she doesn’t want it to live or be a burden to her, this is no mere choice. It’s like what’s happening in China. But if it’s not life, then it’s like removing a wart. A choice between a woman and her doctor. It explains why the Supreme Court doesn’t want to weigh in on when life begins because then another person’s choice might come into play. These people are judges not biologists and sadly, everyone has their own political interests.

I want to tell you my personal journey. Please consider joining me on the next page to read how it applies to the Right Question about Abortion:

How well do we see the Image of God in the unborn?”